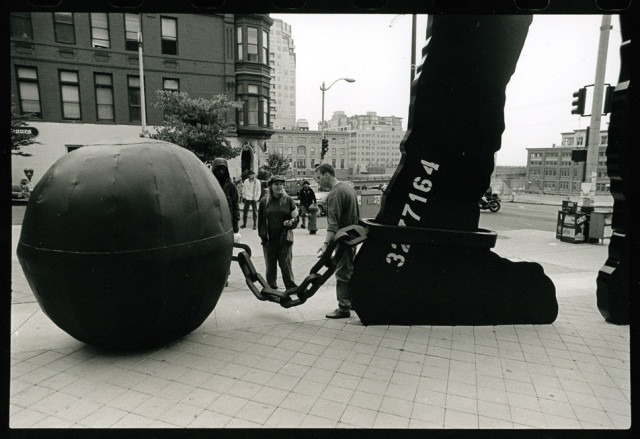

Labor Day, 1993. Jonathan Borovsky’s kinetic sculpture, Hammering Man, which resides outside the Seattle Art Museum (SAM), bore a new attachment: a seven hundred-pound, 19-foot circumference ball and chain, constructed of sheet metal and plate steel. Its cuff was lined with rubber, so as not to damage Hammering Man. There, the guerrilla art piece stood for two days, a statement against working-class oppression, before it was removed on Sep. 8 by the Seattle Engineering Department. And as the attachment was detached, the legend was born.

The culprits were revealed to be a group of 12 guerrilla artists headed by Jason Sprinkle, who went by the moniker, Subculture Joe. Sprinkle was born in 1969 and hailed from Port Orchard, Washington. Wendy Ceccerelli, director of the Seattle Arts Commission at the time, snidely referred to the group as the Fabricators of the Attachment (FA), refusing to refer to them as artists. They claimed the title proudly.

When we first read the name Subculture Joe on a Seattle subreddit, we were immediately intrigued. The ball and chain was a powerful image that felt ahead of its time. Seattle class anxiety was potent in the ‘90s, but the sculpture predated the corporate tech revolution that companies like Amazon and Microsoft brought into Seattle’s economy; before the two wealthiest men in the world, Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, designated Seattle their corporate home.

Class conscious interpretations aside, a 1995 Seattle Times article by Thomas W. Haines featured members of the FA describing the organization’s mission, “‘we’re not activists’… ‘we have many burning issues’… ‘or none.’” Post-ball-and-chain, the FA had a few more projects and became something of an inside joke among Seattleites. But no stunt was so infamous as Sprinkle’s 1996 solo project.

Sprinkle had trained as a welder with the Job Corps, and as a project for them, he had constructed a giant metal heart, which he drove in a truck around the country having Job Corps kids sign. Things weren’t going well for Subculture Joe around this time. Among other things, he was in danger of losing the FA workshop space. In July 1996, Sprinkle parked the truck, tabs expired and metal heart inside, in Westlake Center and punctured the tires.

The heart was not initially perceived as a threat or even an art piece. But, by the end of Jul. 15, 1996, six blocks of downtown Seattle had been evacuated, rush hour traffic was reduced to pandemonium, and the entire Seattle area was watching a bomb squad probe at it. The Seattle Police Department had called the truck in as a bomb threat, citing a signature left by a Job Corps kid in Idaho – “Timberlake Carpentry Rules (The Bomb!)” – as a warning of an explosive device within the truck. Sprinkle, completely shocked by the misinterpretation, turned himself in and was arrested.

After his arrest, Sprinkle was charged with intimidation or harassment with an explosive device. The response was magnified by growing domestic terrorism anxiety from the Oklahoma city bombing a year before. His bail was set at $100,000. He accepted a plea deal and spent a total of 32 days incarcerated. After his release, reflections from friends and family tell of a changed Jason. His public art career was over. In an interview with Seattle Post-Intelligence, a friend of Sprinkle’s, Art Donelly, reflects, “He had a mental breakdown in jail. Besides being brilliant and quirky with a unique slant on the world, he suffered from mental illness. Jail really brought that on. It broke him. He took medications after that, and he was never the same.”

On May 16, 2005, Sprinkle was hit by a freight train while visiting family in Mississippi. There were no witnesses.

We wanted Subculture Joe to be a compelling figure, the voice of a generation. But he wasn’t.

Why do we demand compelling meaning from not only art, but the lives of artists, themselves? In writing this, are we mythologizing Sprinkle and the FA, or worse, sensationalizing them? Kurt Cobain, the patron saint of grunge, not the person, is everywhere. His life has been deified, his visage splashed across t-shirts and tapestries, his private journals published, and, grossly, his suicide note sold and distributed as a piece of poetry. Even the circumstances of his death have been reduced to entertainment fodder and conspiracy.

It’s not hard to find parallels between Cobain and Subculture Joe; two artists whose lives ended tragically. The difference being guerilla sculpture doesn’t exactly gain as much media traction as popular music.

The similarities don’t end there. Like grunge, the FA were given their name and their narrative. Icons of grunge famously hated the word, a marketing ploy, which served only to peddle clothes and records.

But fabrications and myth do not just serve to commodify, they are also integral to the inception, survival, and spread of subculture. In Rick Marin’s infamous New York Times article, “Grunge: A Success Story”, he interviewed Megan Jasper, a saleswoman for Caroline Records and grunge cultural consultant. She provided a supposed lexicon of grunge; instead of hanging out, the youth of Seattle could be found “swingin’ on the flippity-flop.” Were you drunk, or were you a “bloated big bag of bloatation?” Jasper later admitted that most of the slang was made up on the spot for the sake of fun.

The Yippies of the ‘70s, a movement protesting the Vietnam War that developed a unique brand of countercultural action and behavior via political pranks, were hyper-aware of the utility of myth. Abbie Hoffman, remembered as one of the founding members, spoke on the televising of the 1968 Democratic National Convention Protests in his book “Revolution for the Hell of It”, “He [the viewer] makes up what’s going on in the streets. He creates the Yippies, cops, and other participants in his own image. He constructs his own play. He fabricates his own myth.”

Collective stories, regardless of their truthfulness, are key in creating culture and preserving it. In the age of the internet, music subculture has migrated online. Before, word-of-mouth and tall-tales were the lifeblood of subculture, but in an age where everybody is a documentarian, myths are harder to perpetuate. Sprinkle and his FA are an example of organic myth. They represent a phenomenon of connective legend we desire in a disconnected world.

We want the things we identify with to exist for greater purpose and meaning. We crave something that is more than the sum of its parts. We create the gestalt we desire, even if it is just a heightened tale. A game of cultural telephone. And in forging the myth, we forge the movement. The myth is the movement.

Author

Grace Molinaro has spent all her 18 years in Seattle. A barista, astute observer, and communications major at Seattle Central, Grace is interested in all the messy and convoluted ways we grasp for connection. Writing is a lifelong love for Grace. She often says “it’s one of the only passions I will never stop doing, regardless of if there was an audience.” Grace’s other passions include music, theatre, filmmaking, grilled cheese, and Dungeons and Dragons.

Not many actually know about what others call “Subculture Joe” or “Fabricators of the Attachment” (which was actually called Fabricators das de attachment by us in the group) because many were afflicted with the overwhelming amount of meth addictions in the Seattle of the ’90s. I was a part of FddA and installed the heart, and knifed heart in Westlake and the (lesser known to any) Monolith on Capital Hill during the group’s adventures. Pre-Internet, not many of the real stories are left about our gorilla art, but they are a true testament to the powers of the people to shine a light on the truth that was happening at that time and (minimally) should be researched and retold for the massive impact on Seattle’s history that they held outside of the one predominately-known member. There are MANY MORE side stories to the group that has never been told that I was a part of.