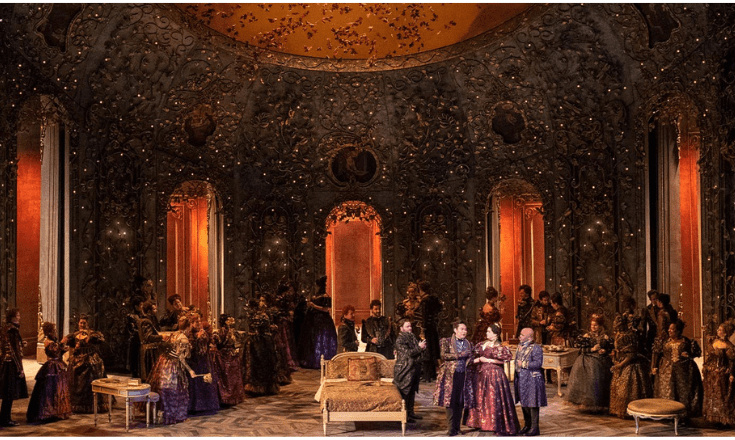

On Oct. 19, 2022, I had the privilege of attending the Seattle Opera’s opening night of “Tristan and Isolde.” Once the public settled in, the lights turned down, and the orchestra commenced Richard Wagner’s famous prelude marked by the Tristan chord. After 12 minutes of pure orchestrated music, and the quiet and attentive souls of the spectators, the curtains went up to reveal actresses Mary Elizabeth Williams and Amber Wagner in the roles of Isolde and Brangäne, respectively, opening the opera’s first act. The spectacle was about 4 hours and 20 minutes long, including its two intermissions.

“Tristan and Isolde,” composed and written by Wagner, tells an old Celtic tale. A tragic romance, similar to “Romeo and Juliet”, but set in the cold winds of Cornwall and the seas that surround Ireland. With no usage of microphones or any amplifying apparatus, opera singers rely solely on their bodies to produce a sound big enough to soar above the entire orchestra and reach the public’s ears with power.

The most popular operas are generally written and sung in either Italian or German, the latter being the case for “Tristan and Isolde.”But don’t fret, there are subtitles accompanying the entire show on a long screen above the stage. Before entering the theater itself, spectators are given a flyer, called a libretto, containing an explanation of each of the play’s acts, characters, and plot. Oftentimes a description of what took place before the story starts is also included, as well as information about the actors and production team. Librettos used to be more detailed in the past, before the advent of subtitle screens, and were usually what the public relied on to further comprehend each act.

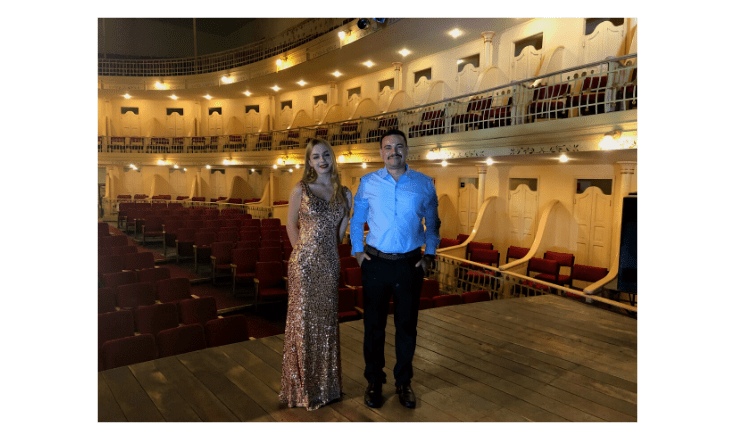

This specific production of Wagner’s work at the Seattle Opera was directed by Marcelo Lombardero, with whom I had the chance to briefly speak with during the post-show talk, which happened inside the theater on the opening night in the first rows before the stage.

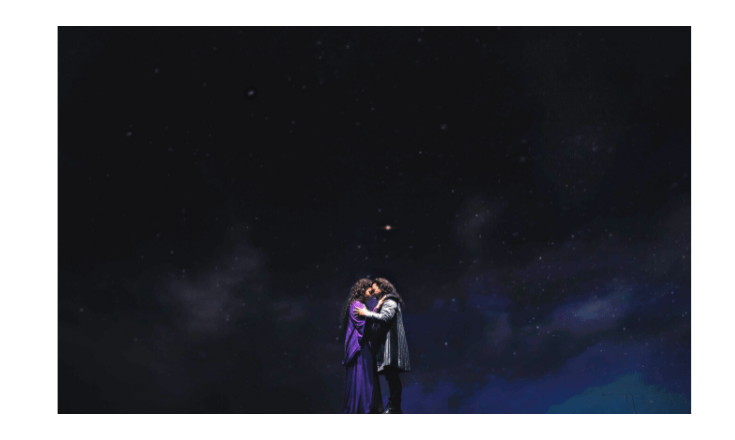

Compared to the number of people who attended the show, the amount who stayed for the talk was minimal. We had the chance to hear first-hand from the show’s production on how it all came to be. Director Lombardero explained that he and his production made the decision to not use any props or physical scenery, relying only on a rising pedestal that was already a part of the stage, and, principally, on video-projections and multiple screens.

Lombardero told us that this decision had arisen from the fact that, in the first years of the production, they did not display much budget at all and had to use creativity to bring it all together. Paraphrasing his words, difficulty leads to creativity, which in turn leads to innovation. Indeed, such a production was innovative: never before had singers been behind a transparent screen, separating them from the audience on which original videos were projected. This front screen paired with other screens behind the actors gave the impression of a much bigger stage with multiple realms. In certain moments, it was as though the whole stage disappeared, giving place to the surrealist image of singers “floating” amongst a starry night-sky, or the tempestuous waves of an ocean (footage which Lombardero revealed was all taken on the coast of Chile and South America by the production team). The two moments in which this happened were certainly my favorites and were very well-placed, for they were held during the two most popular arias of “Tristan and Isolde,” the “Love Duet” (“Liebesnacht”) and “Isolde’s Liebestod.”

Between each act of the play, there were 25 minutes of intermission in which the audience could leave the spectacle room and wander through the theater, sharing their impressions and opinions with fellow members of the public, grabbing cocktails and snacks, or even visiting the souvenir shop on the first floor.

Regarding the common question of what to wear, visitors ranged from full gala gowns, formal attire, and medieval costumes, to Mariners jerseys, shorts, and sneakers. Because watching an opera is such an intrinsic experience, leading you to dive into a fantasy world of your own, the intermissions are opportunities to share that world with other people, even with those you’ve never met before. Likewise to a rock concert, which we may regard to be an extreme-opposite to an opera show, every single person is there for the same reason, regardless of their identity. Some may call that reason music, others may say entertainment, others may address it as beauty or art, but the common link between it all is emotion.

An opera, exactly like any other live music performance or a movie-theater premiere, will speak to each of us in a delicate but very incisive way. As one of my singing professors told me when discussing the difference between singing an opera and singing a German Lied, “Opera is brute. It is big; it depicts fleeting emotions.” In my own words, an opera is a depiction of the most human aspects of our species. From daily life to the feeling of having your heart ripped out of your chest after a lover leaves or during the first stages of grief. It depicts passion, lust, joy, happiness, greed, doubt, anger, fear, and situations that every one of us can relate to. Opera, beloved craft of the human race, unites orchestrated music, singing voices, acting, poetry, language, history, dancing, and visual arts into one spectacle, and, as seen in innovative productions such as the one described above, increasingly incorporates new technology and ideas as well.

There is this idea that opera is segregative and elitist which discourages new audience members from experiencing shows and enjoying the craft. While this idea might have been true for quite a period of time, and still is the No. 1 caricature we think of when the craft is mentioned, opera nowadays is just as accessible as popular music. Full onstage operas, arias, albums, and recitals are available in high-quality on Youtube, Spotify, Podcasts, and any other platform used to stream other kinds of music.

An opera ticket can be expensive depending on the location or production, just like any other live music concert, but there are accessible tickets like the Seattle Opera offerings on rush tickets, priced at $25, an amount of money lower or equal to what we spend to experience our favorite bands on tour. Just like the world of popular music, opera also has gossip, memes, jokes, and a fanbase from all around the world and within all age ranges.

From the perspective of a very dramatic, sensitive person like myself – sometimes affectionately called a drama queen by friends and family – there are sentiments that are oftentimes too big to express in any way other than with the pinnacle of the human voice, itself, often regarded as the most perfect instrument of all. Of course, there are plenty of other feelings that, to me, can only ever be expressed in popular music, like Motörhead ballads, classic Guns N’ Roses’ power chords, Kurt Cobain’s hoarse vocals, or even Lana Del Rey’s melancholy progressions and haunting voice. The only difference is that there is a lack of exposure to opera and the classical music scene within population of several countries, especially in the Western world.

In an opera aria, the composer carefully manipulates his choices to convey a very precise feeling, communicating the thoughts of a character. The poetry or the words of the song allow the spectator to understand the character’s actions within a melody. The orchestration behind them, however, allows us to understand the character’s feelings. A great example is the aforementioned Tristan chord, a revolutionary choice of Wagner within music theory, which conveys the sense of agony, uncertainty, and something unfinished in the plot. As they fall in love, Tristan and Isolde are never to be together, only conjoining their souls and bodies in secrecy and danger. The Tristan chord marks that sense of something unresolved. The chord which completes the progression and musically brings a sense of closure is only achieved by the ending of the opera, when, at last, the protagonists can share their love fully and at peace – in death.

Another wonderful example, which I first heard analyzed in a lecture at Yale University by professor Craig Wright, regards the opera “La Traviata” by Giuseppe Verdi. In the opera’s first act, characters Violetta and Alfredo are infatuated with one another, but Violetta hesitates when Alfredo declares his love for her, thinking of the constraints of marriage and her current life of freedom and bohemia. In this situation, Alfredo sings his signature melody, speaking of love, in a duet with Violetta, who sings a different, more fast-paced melody. Violetta’s melody bears a major key and a faster tempo, matching her character who wants fleeting joy and passion and doubts love. Alfredo’s slower melody bears a key change to minor with longer more serious notes, conveying that he speaks of love and stability. The characters subjectively compete, and, by the end of the song, Violetta is found singing Alfredo’s melody, showing the audience purely with music that she has been convinced, even though her lyrics do not explicitly express it. These compositional subtleties are present in every opera.

Because of its precision and dramatics, we often hear opera arias as soundtracks to specific moments in TV, cinema, and pop culture, such as recent Netflix production, “Wednesday,” with its choice of playing aria “La Mamma Morta” from the opera “Andrea Chénier,” by Umberto Giordano, in episode four as blood rains from the ceiling, ruining a high school prom. In “Stranger Things”, an entire episode was named after Giovanni Paisiello’s opera, “Nina,” which even made it into the plot of the show and was mentioned and explained by a character, making a clear connection between the aria “Il Mio Ben Quando Verrá” (which was the first aria I studied when I began to sing, thus seeing it in a mainstream show was such an exciting moment for me), and the season’s plot. There are several other examples of opera making appearances in popular culture.

In 2018, I attended a Roger Waters’ (Pink Floyd) concert in São Paulo, and the cathartic feeling of being amongst all those thousands of faces in the dark, singing the words to “Time,” and shouting during guitar solos was the very same epiphany of sitting in silence amongst all the other souls as Isolde stands up besides Tristan’s body and opens her heart to sing us her own last words in the final aria of the opera.

With this, I encourage you to listen to classical music and operatic voices, for you may discover a whole new world with which to fall in love with and express your anguishes and joys.

Author

Sophia is an internationally published author with her book Primeira Pessoa, as well as a young classical singer. Born and raised in Brazil, she believes the greatest role of a writer is to bring forth the truth, the honesty, and the humanity that echoes within each one of us.

Be First to Comment